The Biodiversity Heritage Library’s 2 million image archive is now available online for free: http://slate.me/2hQ6Ye3

SlateVerified account @Slate

Politics, culture, technology, business, news, and commentary. Procrastinate better.

Jean Polfus @JeanPolfus

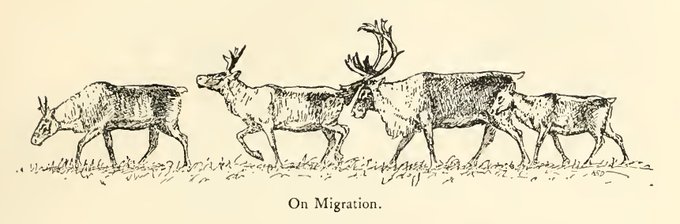

Jean Polfus @JeanPolfus There are some hidden gems in this 1913 book by Arthur Radclyffe Dugmore on Newfoundland #caribou! #biodiversity https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/8856#/summary …

8:07 PM - Nov 4, 2017 · Tulita, Northwest Territories

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/

The Biodiversity Heritage Library’s open-source archive contains wonders of all kinds.

By Eleanor Cummins

#Armadillo for #MammalMonday! A member of the order Cingulata from Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (@Le_Museum) T. 14 (1908). http://s.si.edu/2zkPyha cc @Publi_MNHN

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Illustrations via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

There are thought to be about 10 million distinct species of plants and animals on Earth. That number is incomprehensibly large, not least because most species are still undiscovered. But now the Biodiversity Heritage Library, an open-access repository for some of the most stunning images collected of life on Earth, is helping to make these ecological wonders all the more real: It’s made more than 2 million images of our planet’s biodiversity available online for free. Anyone can explore the expansive collections, study the digitized materials, and even download the images for whatever scientific—or artistic—project you have in mind.

Many of the figures in the library’s collection inspire delight, like this assortment of real-life Harry Potter creatures:

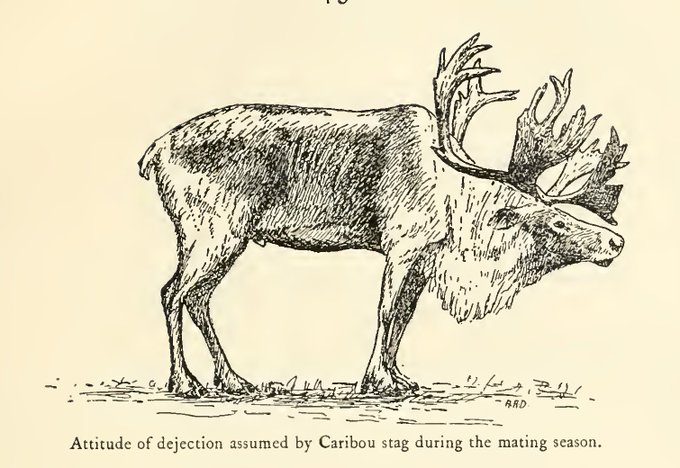

Others offer a good chuckle—I mean, who hasn’t felt like this dejected stag?

But still others are tinged with existential darkness, like an old black-and-white photo of the American bison, the image of a slain eagle, or renderings of other endangered species. They’re another reminder that many scientists believe we’re in the midst of a great extinction, during which huge numbers of species will die en masse, many of them before even being discovered. And unlike past extinctions, which were caused by random shifts in Earth’s atmosphere, this one’s caused by us.

In her 2014 book, The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert suggests the changes the world is undergoing are the result of the so-called Anthropocene, a new geological epoch defined by human dominance and the danger that comes with it. Depending on how you count it, since at least the Industrial Revolution, humans have been reshaping the globe to disastrous results. As a result, Kolbert writes, “it is estimated that one-third of all reef-building corals, a third of all freshwater mollusks, a third of sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles, and a sixth of all birds are headed toward oblivion.”

As Josh Jones writes in a blog post at Open Culture on the newly released series, appreciating biodiversity is perhaps one of the small ways to stop this spiral:

If we want to understand what is at stake besides our own fragile fossil-fuel based civilizations, we need to connect to life emotionally as well as intellectually. Short of globe-hopping physical immersion in the earth’s biodiversity, we could hardly do better than immersing ourselves in the tradition of naturalist writing, art, and photography that brings the world to us.

The archive provides an easy way to remember that beauty.

The depressing decline of biodiversity shouldn’t take away from the thrill of exploring the library’s archive. But it does lend a certain kind of morbid hum to the browsing experience. The collection is certainly chock full of things we’ve lost and things we are currently losing. The only hope is that getting lost in these Flickr files will inspire us to better mitigate the decline we’re seeing in the real world.

One more thing

Since Donald Trump entered the White House, Slate has stepped up our politics coverage—bringing you news and opinion from writers like Jamelle Bouie and Dahlia Lithwick. We’re covering the administration’s immigration crackdown, the rollback of environmental protections, the efforts of the resistance, and more.

Our work is more urgent than ever and is reaching more readers—but online advertising revenues don’t fully cover our costs, and we don’t have print subscribers to help keep us afloat. So we need your help.

The Biodiversity Heritage Library’s open-source archive contains wonders of all kinds.

By Eleanor Cummins

#Armadillo for #MammalMonday! A member of the order Cingulata from Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (@Le_Museum) T. 14 (1908). http://s.si.edu/2zkPyha cc @Publi_MNHN

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Illustrations via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

There are thought to be about 10 million distinct species of plants and animals on Earth. That number is incomprehensibly large, not least because most species are still undiscovered. But now the Biodiversity Heritage Library, an open-access repository for some of the most stunning images collected of life on Earth, is helping to make these ecological wonders all the more real: It’s made more than 2 million images of our planet’s biodiversity available online for free. Anyone can explore the expansive collections, study the digitized materials, and even download the images for whatever scientific—or artistic—project you have in mind.

Many of the figures in the library’s collection inspire delight, like this assortment of real-life Harry Potter creatures:

Others offer a good chuckle—I mean, who hasn’t felt like this dejected stag?

But still others are tinged with existential darkness, like an old black-and-white photo of the American bison, the image of a slain eagle, or renderings of other endangered species. They’re another reminder that many scientists believe we’re in the midst of a great extinction, during which huge numbers of species will die en masse, many of them before even being discovered. And unlike past extinctions, which were caused by random shifts in Earth’s atmosphere, this one’s caused by us.

In her 2014 book, The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert suggests the changes the world is undergoing are the result of the so-called Anthropocene, a new geological epoch defined by human dominance and the danger that comes with it. Depending on how you count it, since at least the Industrial Revolution, humans have been reshaping the globe to disastrous results. As a result, Kolbert writes, “it is estimated that one-third of all reef-building corals, a third of all freshwater mollusks, a third of sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles, and a sixth of all birds are headed toward oblivion.”

As Josh Jones writes in a blog post at Open Culture on the newly released series, appreciating biodiversity is perhaps one of the small ways to stop this spiral:

If we want to understand what is at stake besides our own fragile fossil-fuel based civilizations, we need to connect to life emotionally as well as intellectually. Short of globe-hopping physical immersion in the earth’s biodiversity, we could hardly do better than immersing ourselves in the tradition of naturalist writing, art, and photography that brings the world to us.

The archive provides an easy way to remember that beauty.

The depressing decline of biodiversity shouldn’t take away from the thrill of exploring the library’s archive. But it does lend a certain kind of morbid hum to the browsing experience. The collection is certainly chock full of things we’ve lost and things we are currently losing. The only hope is that getting lost in these Flickr files will inspire us to better mitigate the decline we’re seeing in the real world.

One more thing

Since Donald Trump entered the White House, Slate has stepped up our politics coverage—bringing you news and opinion from writers like Jamelle Bouie and Dahlia Lithwick. We’re covering the administration’s immigration crackdown, the rollback of environmental protections, the efforts of the resistance, and more.

Our work is more urgent than ever and is reaching more readers—but online advertising revenues don’t fully cover our costs, and we don’t have print subscribers to help keep us afloat. So we need your help.

Eleanor Cummins is an intern at Slate. Her reporting interests run the gamut of science.

This mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) calf is ready to show off on the #archivecatwalk! #SciArt by C. Berjeau & published in "Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London" 1872. Digitized by @NHM_Library http://s.si.edu/2izzTQB #ExploreArchives

No comments:

Post a Comment