Sunday, 31 December 2017

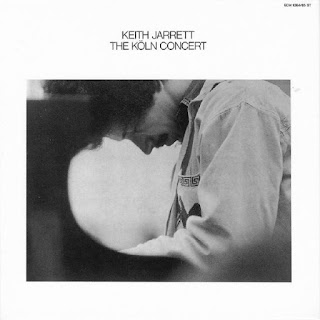

Keith Jarret “The Köln Concert” 1975

(50 Greatest Live Albums of All Time Rolling Stone)

(500 Greatest Albums All Of Time Rolling Stone)

Keith Jarret “The Köln Concert” 1975 50 Greatest Live Albums of All Time (Rolling Stone) (500 Greatest Albums All Of Time Rolling Stone)

full on google+https://photos.app.goo.gl/MseIu07wsdXUwMm62

Keith Jarrett piano

Recorded January 24, 1975 at the Opera in Köln, Germany

Thirty-six years ago, Keith Jarrett, the now 65-year-old pianist and composer from Allentown, Pennsylvania, crossed a chasm usually unbridgeable for either jazz or classical performers – and this virtuoso happens to be both.

Thirty-six years ago, Keith Jarrett, the now 65-year-old pianist and composer from Allentown, Pennsylvania, crossed a chasm usually unbridgeable for either jazz or classical performers – and this virtuoso happens to be both.

Jarrett’s message from the keyboard took off from the small enclave of an informed and dedicated minority audience, and reached the huge worldwide constituency of listeners. His albums would turn up in the collections of people who would otherwise cross the street to avoid buying a jazz record. From the mid-70s on, his concerts began to resemble religious rituals, attended by flocks of devotees for whom his music had a meditative, spiritual and transformative power. And all this stemmed from the recording of a single album – conceived as a live concert by a sleep-deprived Jarrett on a faulty grand piano – made in Köln, Germany, on 24 January 1975. Sales of The Köln Concert, on Munich’s fledgling new-music label, ECM, broke records of all kinds. It remains the bestselling solo album in jazz, and the bestselling solo piano album in any genre.

From the glistening, patiently developed opening melody, through sustained passages of roaring riffs and folksy, country-song exuberance, the pianist is utterly inside his ongoing vision of the performance’s developing shape – a fusion of the freshness of an improvisation with the symmetries of a composition that’s central to the album’s communicative power. Harmonically and melodically, it wasn’t a particularly “jazzy” record by the piano-jazz standards of that time, which might also have eased its progress across the sectarian divides of jazz, pop or classical tastes. There had been, however, an earlier clue to the possibilities of this journey into the largely uncharted waters of improvised solo-piano performance. The great pianist Bill Evans, one of the young Jarrett’s jazz models and an artist similarly steeped in classical music, had recorded the meditative solo improvisation Peace Piece 16 years before, and built it around a simple two-chord vamp in which the harmonies stretched increasingly abstractly as the performance progressed. Much of Jarrett’s playing on The Köln Concert similarly developed around repeating hook-like motifs, instead of unfolding over song-structure chord sequences as most bop-based jazz solos did.

Jarrett’s improvisation was also hypnotically rhythmic, bordering on mantra-like. He was unafraid to locate a compelling idea and stick with it, building intensity on a single rhythmic notion in a manner that still sounds urgently contemporary. A pop-like deployment of repetition, and a reassuringly anchored sense of tonal consistency – the latter occasioned by the pianist’s hugging of the acceptable middle-register of an otherwise tinny piano he had almost cancelled the gig to avoid – contributed to the music’s astonishingly organic feel.

Jarrett’s desire to make a solo-piano album had led to his earlier departure from Columbia Records, and to his relationship with the compatible Manfred Eicher of ECM (with whom he was travelling around Europe, jammed into a Renault 5, on the tour that included Köln), a visionary producer who heard new music in the same eclectic way. Though he was only 29 at the time of The Köln Concert, Jarrett had already had a brief flirtation with electronics in Miles Davis’s fusion band (declaring afterwards that he wouldn’t touch a plugged keyboard again) and rich regular-jazz and early-fusion experiences in the popular bands of saxophonist Charles Lloyd and drummer Art Blakey. He had also made some compositionally distinctive and now highly regarded postbop recordings of his own, in the legendary early-70s “American quartet” with saxophonist Dewey Redman, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Paul Motian. But Köln was Jarrett’s moment, and a turning point for the immensely influential ECM label too, which the album helped to bankroll for years to come.

The Köln Concert isn’t universally admired by jazz listeners. Some find it close to easy listening in its repetition of catchy melody, or a irreconcilable split from the jazz tradition in its avoidance of many of the genre’s familiar materials. But Jarrett’s remarkable output in the years since, his interpretations of classical works, reinvention of the Bill Evans-inspired conversational trio, engagement with everything from symphony orchestras to cathedral organs, and through it all an enduring popularity that sells out the world’s great concert halls months in advance, testify to his creativity and eloquence.

In 2006, he released a similarly unpremeditated solo-piano concert from Carnegie Hall that ran to 90 minutes and five encores. When I discussed it with him for the Guardian, Jarrett said: “My glasses were falling off, my pants were twisted up, I was sweating, crouching, standing up, sitting down, and I was thinking ‘nothing can stop me now’.” He also said he’d had the same feeling – of total trust in his imagination – on The Köln Concert more than 30 years before….by…John Fordham……~

Circumstances were inauspicious when pianist Keith Jarrett and ECM Records owner-producer Manfred Eicher rolled into Cologne, Germany, in January of 1975. Jarrett hadn’t slept the night before and was in pain. Worse, the Bösendorfer piano they’d requested had been replaced by an inferior model which, according to Jarrett, “sounded like a very poor imitation of a harpsichord or a piano with tacks in it.” Yet the hour-long solo concert he performed around midnight at the city’s opera house, wearing a brace and nearly falling asleep at his instrument, was a deeply entrancing meditation on rhythm, whose double-vinyl recording became both the best-selling solo jazz and solo piano albums in history. Jarrett’s extemporized fantasia drifts seamlessly from idea to idea, sometimes settling into a two-chord vamp for minutes at a time. More relaxed than most of his other solo recordings, it boasts a full complement of Jarrett’s whooping, sighing and foot-stomping affectations while still offering a ravishing introduction to the art of improvisation. Richard Gehr…Rolling Stone..~

Recorded in 1975 at the Köln Opera House and released the same year, this disc has, along with its revelatory music, some attendant cultural baggage that is unfair in one sense: Every pot-smoking and dazed and confused college kid – and a few of the more sophisticated ones in high school – owned this as one of the truly classic jazz records, along with Bitches Brew, Kind of Blue, Take Five, A Love Supreme, and something by Grover Washington, Jr. Such is cultural miscegenation. It also gets unfairly blamed for creating George Winston, but that’s another story. What Keith Jarrett had begun a year before on the Solo Concerts album and brought to such gorgeous flowering here was nothing short of a miracle. With all the tedium surrounding jazz-rock fusion, the complete absence on these shores of neo-trad anything, and the hopelessly angry gyrations of the avant-garde, Jarrett brought quiet and lyricism to revolutionary improvisation. Nothing on this program was considered before he sat down to play. All of the gestures, intricate droning harmonies, skittering and shimmering melodic lines, and whoops and sighs from the man are spontaneous. Although it was one continuous concert, the piece is divided into four sections, largely because it had to be divided for double LP. But from the moment Jarrett blushes his opening chords and begins meditating on harmonic invention, melodic figure construction, glissando combinations, and occasional ostinato phrasing, music changed. For some listeners it changed forever in that moment. For others it was a momentary flush of excitement, but it was change, something so sorely needed and begged for by the record-buying public. Jarrett’s intimate meditation on the inner workings of not only his pianism, but also the instrument itself and the nature of sound and how it stacks up against silence, involved listeners in its search for beauty, truth, and meaning. The concert swings with liberation from cynicism or the need to prove anything to anyone ever again. With this album, Jarrett put himself in his own league, and you can feel the inspiration coming off him in waves. This may have been the album every stoner wanted in his collection “because the chicks dug it.” Yet it speaks volumes about a musician and a music that opened up the world of jazz to so many who had been excluded, and offered the possibility – if only briefly – of a cultural, aesthetic optimism, no matter how brief that interval actually was. This is a true and lasting masterpiece of melodic, spontaneous composition and improvisation that set the standard….by Thom Jurek…allmusic…~

This lodestar 1975 set didn’t just prove that an improvised solo jazz piano record could find a mass audience; it also helped solidify the intense yet dreamy aesthetic of producer Manfred Eicher’s then-young ECM label. Jarrett lets loose a torrent of ideas on the piano, delighting even himself (which you can hear whenever he lets out one of his frequent vocalizations or foot-stomps). Whether he’s ferociously plugging away at a vamp or slowly building out a tender theme, he keeps a spellbinding intimacy central to his sound….~

I still remember my first encounter with Keith Jarrett’s album The Köln Concert, recorded 40 years ago this week.

I was a teenager browsing the jazz bins at a record store on El Camino Real in Palo Alto late one evening, when a store clerk put the new Jarrett record on the turntable. As the opening notes began reverberating through the aisles, I could immediately sense a change in the ambiance of the store. Customers looked up from the merchandise, and gradually focused their attention on the ethereal piano music coming out of the speakers.

Then something unexpected happened. Within a couple of minutes of the album going on the turntable, a customer walked up to the front desk to ask the name of the record. He immediately bought a copy. Soon a second customer did the same. Then a third. And a fourth.

Within ten minutes, the store’s entire stock of The Köln Concert had sold out.

Frankly, I was as surprised as the store clerk. I was very familiar with Jarrett’s work, and had just seen him perform a few months earlier with his quartet at an Oakland concert. I considered myself an admirer, and had recently devoured—that is not too extreme a word to use, given my enthusiasm—his two previous solo piano albums, Facing You and Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne. I knew his music inside and out, had studied it with the goal of unlocking its essence. But I was a jazz piano player who spent three hours per day in the practice room; latching on to a new Jarrett album was a natural thing for me to do. The real mystery was why all these other customers, who had been browsing through the rock and pop bins, were responding with so much enthusiasm.

One thing, however, was absolutely clear to all of us. Jarrett’s album didn’t sound like anything else in the music world in the mid-’70s. I was a college student at the time, and the most widely-played albums on campus were Frampton Comes Alive, Fleetwood Mac, and Songs in the Key of Life. Disco was still intensely popular and, in a few months, The Sex Pistols would record their first album. The Köln Concert, a shimmering and rhapsodic solo piano album, was nothing like any of those records.

Even when compared to jazz albums, Jarrett’s new sound was an outlier—this was, after all, the age of jazz-rock fusion, and the biggest-selling bands in the field were plugged-in electric groups. The hot jazz acts of the day were Weather Report, George Benson, and the high-octane fusion bands led by Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock.

The Köln Concert was the opposite of all that. Jarrett not only played the grand piano (increasingly referred to as the acoustic piano, at that juncture, to differentiate it from the electric keyboards of the era), but he played it with a degree of sensitivity and nuance that you couldn’t find elsewhere in commercial music. He even risked gentleness and sentimentality, with a heart-on-sleeve emotional directness that many jazz artists would have been embarrassed to emulate—especially in the mid-’70s, when irony was in the ascendancy as a cultural attitude.

Yet, in the coming months, I watched with amazement as The Köln Concert entered the mainstream culture, reaching an audience that I might have thought immune to the appeal of jazz piano. It eventually sold more than 3 million copies, and for a time ranked as the top-selling solo piano album in history.

And Jarrett did this by violating almost every rule of commercial music. The tracks on The Köln Concert were free-flowing spontaneous improvisations recorded live in concert in Germany. They lacked a holistic structure. Even worse, they were much too long for radio airplay. The opening cut was 26 minutes in duration, and the next two tracks were 15 minutes and 18 minutes long. Only the seven minute encore followed something resembling a song form, but even this sounded a world apart from the hit singles of the day.

You might think that jazz radio deejays would embrace this music. But even they were skeptical. The Köln Concert avoided most of the familiar syncopations and phraseology that permeated the other jazz albums in heavy rotation. Programming directors feared that they might alienate their core audience if they played music of this sort that, after all, didn’t really sound jazzy.

Yet somehow Jarrett bypassed radio, and managed to go viral via the oldest method of all, word of mouth and person-to-person contact with friends who already owned the record. These were people who didn’t listen to jazz radio anyway.

Huge sales are not always greeted with enthusiasm in the jazz community, and a backlash was inevitable in the case of The Köln Concert. But the emotional directness of the music, and its unabashed melodicism made this album especially open to critique from those who felt the jazz art form required something more abrasive and challenging to move forward. When the New Age music scene blossomed a few years later, with numerous imitators of lesser talent mimicking (and diluting) the aesthetic vision of the Köln improvisations, perhaps even Jarrett himself wondered at what he had wrought

I understand these criticisms, but don’t agree with them. Jarrett tapped into something fresh and honest at that concert. He created a visionary work that still rivets the attention of first-time listeners today—much as it did on that day in the mid-’70s when I first heard it in a retail outlet. The music has held up, indeed much better than many of the irony-laden projects that seemed so much more progressive at the time.

My only regret is that most of the audience that discovered Keith Jarrett with The Köln Concert never embraced the rest of his oeuvre. I would have been delighted to see Facing You or the Bremen concert or the Jarrett quartet albums of the period—and those of other deserving jazz artists—also find a crossover audience. From that perspective, the promise of The Köln Concert was never fulfilled.But I don’t blame Keith Jarrett for any of this. And he certainly can’t be faulted for his banal imitators, or chided for his sales. For his part, he hadn’t been aiming for a hit record, and (unlike many of his contemporaries on the jazz scene) never made the slightest attempt to jump on trends, or even embrace the accepted formulas of commercial records. Moreover, he never tried to recreate the special ambiance of the Köln performance. He viewed this concert as a one-time event. He simply trusted in his music, in his preparation and talent, and then bravely thrust himself into the inspiration of the moment. And, after all, isn’t that what jazz is all about?…by…TED GIOIA …~

I have a friend who is one of the kindest, most generous and straight forwardly nice people that there could be and yet he is very, very irritating. I once shared a house with him and after 12 months I wanted to strangle him and bury him in the cellar. I have the same sort of uncertain response to Keith Jarrett. I came to jazz in my late teens and like many people of my generation it was through Miles Davis’ electric music - but at about the same time I happened to hear Keith Jarrett on an arts TV program and it blew my mind (as we no longer used to say back then because it was too old fashioned). I found his playing stunning - it was all solo work on the program - but I also found the idea of him coming onto the stage without a plan and just improvising for an hour or however long stunning. And that is what he does here. Perhaps because he was one of my first loves when I was responding to music in a new way - I was trying to listen to and understand the music as music rather than thinking about the words (I was a big Dylan fan through my teens) - Jarrett’s music always has a big emotional impact on me, but perhaps some of my uncertainty is that I want to distance myself from the 19 year old enthusiast. The strengths of this album seem obvious: it is a tour de force, it is accessible while seemingly complex, it is impassioned. A basic technique, method (I’m uncertain how to term it) during this concert is that with his left hand he plays rhythmic repetitions, at times sounding like the rhythmic loops in Steve Reich’s music, while with his right hand Jarrett plays exquisite melodies, often sounding deeply Debussian, yet always having a jazz sensibility - despite drawing on European concert music he always remains within the traditions of black American music. Part of the exhilaration of the music is that it brings together seemingly incompatible styles or forms and successfully synthesizes them. I’ve written in other reviews of Jarrett about the irritations of the music: easy hooks holding things together, a tendency to wallow in prettiness, the emotionally lazy effects. I don’t, however, regard his tendency to go on and on to be one of his faults: on this album, as on other concert recordings, it is the longer tracks that are the strongest - Part I and the second section of Part II. The shorter tracks can quickly show his irritations - the final section of Part II lazily keeps to its very beautiful melody but doesn’t do much with it, in the first section of Part II the repetitions dominate the variations - while in the longer tracks his strengths overwhelm the weaknesses. Although I find it a bit puzzling why this was the Jarrett album - and one of the few jazz albums - that seems to have reached out to a broader public, it remains a remarkable performance….by….onethink …~

The story behind this album always makes me think of Elvis Costello’s show in Utrecht on January 24 2005. It was a cold and snowy day in the Netherlands and Costello was having a cold. After a few songs he had very little voice left. When the audience convinced him to continue anyway he gave what is probably the best show I’ve ever seen him play. Sometimes singing around the high notes, missing a few notes or coughing in mid sentence, but the audience didn’t mind. Costello played with more intensity than he had in years and delighted the audience with a few surprising songs in the setlist. It was an unforgettable evening.

Exactly 30 years earlier, January 24 1975, Keith Jarrett arrived in Köln, tired after a long trip from Zürich, not having slept for 2 days and being forced to play on a poor, out of tune grand piano. After the concert promoter had to convince him to perform anyway, he gave a wonderful performance that remains his most popular recording ever and the best selling solo piano and solo jazz album. The piano had lots of shortcomings with malfunctioning pedals and weak low notes, but Jarrett works around it all and like Elvis Costello 30 years later in Utrecht the less than ideal circumstances inspire him to perform with an intensity rarely heard in music.

Strange, melodic, intense, experimental, beautiful, never boring, this remains one of the finest examples of jazz improvisation and solo piano music. With the music being so fascinating you don’t even hear the piano is out of tune or that the low notes sound very weak; it’s simply impossible to pay attention to anything else than the wonderful music. The fact that it was made in such difficult circumstances and that it’s all pure improvisation (Jarrett hadn’t made up a note of these 2 pieces before entering the stage) makes it even more remarkable. If you’re into jazz and for some reason haven’t heard this yet, go get it now. You really need it….by….mdekoning ….~

Amazing

This is an incredible achievement. I was hooked when listen to the first half of Part I. It was probably one of the most beautiful and inspired piece of music I have ever heard. The same thing happened with first part of Part II B.

The rest is also great but these moments are simply amazing. I cannot imagine how Keith managed to play this only by improvising. I don’t want to say anything more. Just listen and enjoy because this is from high spheres. Probably we are not supposed to hear something like this on this existence in flesh and bones….by…petrica …~

I have a confession to make. One that borders on blasphemy for a professed ECM fanatic such as myself: before writing this review I had never heard The Köln Concert. What is perhaps the most highly revered, and certainly the best-selling, album in the ECM catalog has managed to escape my ears all these years. Part of me wanted to save the experience for the right moment, while another had possibly been afraid that I might not like the album. Whatever the reason, I am happy to say that the wait is over…and it has been more than worth it.

The story behind this recording has, of course, already become the stuff of legend. On a dreary January day in 1975, Jarrett arrived at the Köln (Cologne) Opera House fatigued and malnourished and was bid to play on an inferior piano designed for rehearsals and not for live performance. As a result, the concert was almost never recorded. One can read about Köln lore ad nauseum elsewhere, not least in the album’s liner notes, so let’s have nothing more to do with it. The Köln Concert deserves to be listened to as it was created: without borders and without assumptions. And so, last night, as I lay awake in bed unable to sleep, I decided that it was time to fill this gaping hole in my listening life. With the lights already off, I put on the album and let the music take me wherever it wanted to take me. All I can offer in return is the following “travel diary” in honor of Jarrett’s achievement.

The opening chords of Part I set us upon an almost otherworldly path, providing gospelly signposts along the way to remind us of home. The music brims with the need for release, but Jarrett seems to want to hold onto it for as long as he can before its messages are lost forever. There is a persistence to his playing that speaks of countless internal dialogues all vying for attention. Delicate phrasing is suddenly punctured by a rhythmic depressing of the sustain pedal before flowering into an open exposition of higher energy. The music cascades as Jarrett’s voice careens off its towering contours when, just as suddenly, the majesty is swapped for an intimate chamber within its walls. Shadows of a former empire loom large, tethered by ecstatic cries.

Jarrett picks up the pace during the second act, moving from the elegiac to the frantic. Everything “fits,” joined by the same threads: a patchwork in which every seam is uniformly sewn. The progression is as lush as can be. It is as dense as a forest, and just as ordered in its own way. Jarrett brings us to a clearing, only to make us aware of the silence we left behind. So we turn around and jump right back into the thick of things as he expands his architecture to greater depths, carving out a subterranean labyrinth of cavernous sound that will never be charted again. The encore (labeled “Part IIc”) is both a montage of what came before and a preview for that which has yet to arrive.

It might seem clichéd to write this, but sometimes there are moments in one’s musical life that are simply magical. Clearly, Jarrett experienced over an hour’s worth of such moments here, and we are fortunate enough to be able to experience them ourselves, if only vicariously through the mediation of technology. Jarrett seems to know the piano’s vocabulary as well as his own speech, which might very well explain the involuntary vocalizations for which he is so often criticized. Structurally, the album could hardly be simpler: a series of vamps provide ample ground for floating improvised lines that stick primarily to the piano’s middle range. And yet, the scope of his vision is staggering in its implications. Jazz is Jarrett’s anchor, even if the voyage does carry him far beyond its generic boundaries. The applause only heightens the spell, reminding us that what we have just heard is indeed of this world, and was shared spontaneously with a crowd of our peers.

Despite what some might have you believe, by no means should this be anyone’s only Keith Jarrett experience. It needn’t even be one’s introduction. As sublime as it is, it is but one of many formative and breathtaking examples of his prolific output. This album is a lullaby for anyone who has no need for slumber, and Jarrett’s heartfelt voice explicitly conveys the rapture of living in the moment, his vocal interjections enhancing the “live” feel considerably and making for an even more visceral document….by…TYRAN GRILLO…~

Keith Jarrett is known as one of the best jazz musicians of all time, and this, the best-selling solo album in jazz history and the best-selling piano album, is the obvious reason why. Recorded at the Köln Opera House in 1975, this 66 minute solo piano concert manages to cover most every aspect of jazz improvisation to perfection.

This is some of the best jazz improvisation you will ever hear. Actually, I think that whether you like this album or not tells whether you like improv jazz or not. Keith Jarrett has skills. I mean, hearing this masterpiece of more than an hour’s worth of continuous, lush music, it is hard to believe that every note is spontaneous. Jarrett always seems one step ahead; being able to improvise over a two-chord vamp for 8 minutes while still keeping the listener hooked in emotionally; perfectly balancing focus on rhythmic figures, and meditation (at times, bordering to virtuoso self-oscillation) on droning harmonies and moody grooves.

Jarrett opens the concert by quoting the melody of the signal bell in the Köln Opera, which, very fittingly, is normally used to announce the beginning of a concert to patrons. From here on, he fluently pecks around various advanced harmonies, recalling his efforts from fusion-jazz, before diving into 12 minutes of extensive improvisation over a two-chord vamp. It is very trance-inducing but then again, the music is always moving and evolving; even when the foundation that is the bass seems repetitive, there is constantly little variations, which is truly impressive to witness, and so, even though it may at times seem mad and self-oscillating repetitive, you never doubt Jarrett’s genius nor the fact that you will be able to finally see the big picture of something that is purely spontaneous. I mean, the really impressive thing about The Köln Koncert is the feeling of an hour-long improvisation as being something meticulously planned because everything fits so perfectly into a whole.

The shear thought of all of this being improvised is impressive enough to leave you breathless, especially because it’s not only flawlessly executed; it is also full of personality. This album makes it obvious why Keith Jarrett is not only considered one of the absolute greatest jazz musicians of his own era but as one of jazz music’s most outstanding representatives….sputnik…~

The most improbably exhilarating record I’ve ever heard was recorded 40 years ago, at a special late show in the Cologne Opera House, in front of a youthful capacity crowd. It’s likely the only opera-related album I’ve ever listened to more than once, but that’s fitting, since few of the 1,400 young Germans in attendance on January 24, 1975 were regulars, either. They’d come that night to hear something even rarer and less commercial: an hour-long improvisation on solo piano by a 29-year-old Pennsylvanian named Keith Jarrett.

Perhaps you think that 60 minutes of unbroken, off-the-cuff doodling sounds indulgent and esoteric, in which case you’ve never heard The Köln Concert, the double-LP of the show released later that year. Perhaps you think that an entirely improvised live jazz album by a single musician must have been, at best, a cult object, in which case it might surprise you to learn that it turned Jarrett into one of the least likely pop stars in history; to date, it has sold an estimated 3.5 million copies, placing it alongside Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue as one of the most popular jazz records ever. By decade’s end, Jarrett would be release a 10-LP (!!!!) live album and perform solo on Saturday Night Live. In the words of Guardian jazz critic John Fordham, “His concerts began to resemble religious rituals, attended by flocks of devotees for whom his music had a meditative, spiritual, and transformative power.” The mid-'70s were a wild time.

When he arrived in Cologne, Jarrett was a young performer but a seasoned one, with nearly a decade of professional jazz-making already behind him. He’d played piano for saxophonist Charles Lloyd before joining Miles Davis’s band in 1970 and switching over to keyboard. This was a particularly tumultuous moment for Davis—his music had become unprecedentedly dense, expansive, and rhythmic, with songs often stretching to nearly a half-hour and featuring multiple drummers and bassists. The two Miles records that included Jarrett—Live at the Fillmore and Live-Evil—are some of the most frenzied and aggressive jazz ever put to tape, full of long, minimally harmonic arrangements and feral soloing. This was jazz as Afro-futurist squall, a Jackson Pollock deconstruction of Duke Ellington’s famed “jungle sound” from the 1920’s. But Jarrett, a seeker type and a musical prodigy, needed more space for expression than that hurricane allowed.

He left the group in December 1971 and was soon approached by Manfred Eicher, a German national who had recently started his own imprint, ECM Records. Eicher lured Jarrett with the promise of absolute artistic freedom, and the pianist obliged with a studio recording, Facing You, made up of solo improvisations. The polar opposite of Davis’s cacophony, this playing was marvelously clean, direct, and acoustic, as approachable as pop without any of the rock-audience pandering that marked many fusion groups of the time. The record was a small success, particularly among jazz fans, and Eicher decided to take Jarrett on the road.

Europe was in many ways a more friendly audience for jazz musicians than America at the time. While the number of Stateside jazz clubs shrank throughout the '60s, the music was brandished by younger Europeans as a revolutionary totem. Artists from throughout the continent, like Poland’s Tomasz Stanko and Norway’s Jan Garbarek, endowed jazz with new tonalities that strayed far from the blues, bop, or cool modal approaches developed in the U.S. But European audiences were also hungry for American performers, and Jarrett was a known quantity, having toured prodigiously overseas as a member of Lloyd’s and Davis’s bands. Eicher started him on a regular circuit of European markets whenever his schedule allowed, and Jarrett developed his fully improvised style in places like Bergamo, Bern, Geneva, and Molde. Most nights he would play two half-hour movements followed by a five-minute encore; a typical performance would glide between extended, almost gospel-like rhythmic passages and lyrical, balladic sections, often devolving into freer, atonal moments along the way.

Jarrett became a phenomenon, as much for the audacity of his method as for the strangeness of his stagecraft. He often resembled a gymnast more than a pianist—standing up, wildly contorting his arms, breathing heavily, and chanting along with his melodies. His concerts were feats of athletic as well as creative stamina, but there was a deep spiritual element to them as well, as Jarrett made clear in the liner notes for his first live ECM recording, the triple-LP set Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne, released in 1973. Declaring himself to be on a distinctly untrendy “anti-electric crusade,” Jarrett further explained himself:

I don’t believe I can create, but that I can be a channel for the Creative. I do believe in the Creator, and so in reality this is his album through me to you, with as little in between as possible on this media-conscious earth.

This kind of vague religious psychobabble and pop-skepticism likely fits well within your conception of 1973, the heyday of Mother Earth News, Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps, and the Back to the Land and communal-living movements. Within a few years, DownBeat would describe Jarrett’s droning, meditative sections as “sonic mandalas,” while Melody Maker would suggest that his music enforced a “hands clasped and kaftans on” vibe. But the very fact that his music was being covered in the pop-minded and jazz-averse Melody Maker at all was proof of how deeply aligned Jarrett was with other musicians of the time: He evinced and echoed the passionate drones of Ravi Shankar, the purposeful repetitions of James Brown, and the wildly ambitious structures of Soft Machine and Yes, not to mention the proud sonic primitivism of Neil Young.

Which is all to say, the world was ready for The Köln Concert, or at least more prepared for it than might be assumed 40 years on. Certainly the mood was right in the opera house itself, where Jarrett was booked as the fifth show in the so-called Jazz at Cologne series, organized by a teenaged aficionado named Vera Brandes. Selling tickets at only four German marks apiece, Brandes ensured a full house, almost all of the attendees around Jarrett’s age. For his part, he took the stage looking “fresh from the musical Hair,” as one onlooker recently told the BBC….by…John Lingan….~

If blogs had been around in the late 70s or the 80s I wouldn’t have thought for a second to write about Keith Jarrett’s watershed album The Köln Concert, because every jazz enthusiast with a computer keyboard and a Blogger account would have already been flooding the internets with praise about this record. Three and a half decades after its 1975 recording and subsequent release, it remains the record people most identify with Jarrett, and in all likelihood, ECM Records’ all time best seller. But enough time has passed to reflect again on the significance of this record, a timeless recording whose fame was nevertheless rooted in the timing of its release.

By the mid 70s, jazz was dominated by rock-jazz fusion. This sub-genre of jazz had gotten off to a terrific start, but eventually, much of it became over-composed, over-produced and full of bravado. What was gained in proficient musicianship was more than countered by the loss of swing, soul and substance. Sure, there were some notable fusion records of that era and many of them even raved on here, but increasingly, jazz-rock was offering little to offer over what you could get from rock itself. Some of jazz’ most respected players like Jackie McLean, McCoy Tyner and Dexter Gordon stubbornly stuck with acoustic post-bop jazz and paid the price by being driven into obscurity and in some cases, near poverty.

The first flicker of hope in the eventual resurgence of unplugged jazz came one day in January, 1975 when Keith Jarrett sat in front of piano in a Köln, West Germany opera hall and began to play melodies that didn’t exist before that moment. A few years earlier, Jarrett had ironically been a soldier in the movement to rockify jazz as a member of Miles Davis’ band for about 18 months from 1970 to 1972. It’s a stint he’s since disowned, and not long after he left, Jarrett became as likely to play any plugged-in instrument as Marie Osmond was likely to have a tryst with George Clinton.

Keith Jarret “The Köln Concert” 1975 50 Greatest Live Albums of All Time (Rolling Stone) (500 Greatest Albums All Of Time Rolling Stone)

full on google+https://photos.app.goo.gl/MseIu07wsdXUwMm62

Keith Jarrett piano

Recorded January 24, 1975 at the Opera in Köln, Germany

Thirty-six years ago, Keith Jarrett, the now 65-year-old pianist and composer from Allentown, Pennsylvania, crossed a chasm usually unbridgeable for either jazz or classical performers – and this virtuoso happens to be both.

Thirty-six years ago, Keith Jarrett, the now 65-year-old pianist and composer from Allentown, Pennsylvania, crossed a chasm usually unbridgeable for either jazz or classical performers – and this virtuoso happens to be both. Jarrett’s message from the keyboard took off from the small enclave of an informed and dedicated minority audience, and reached the huge worldwide constituency of listeners. His albums would turn up in the collections of people who would otherwise cross the street to avoid buying a jazz record. From the mid-70s on, his concerts began to resemble religious rituals, attended by flocks of devotees for whom his music had a meditative, spiritual and transformative power. And all this stemmed from the recording of a single album – conceived as a live concert by a sleep-deprived Jarrett on a faulty grand piano – made in Köln, Germany, on 24 January 1975. Sales of The Köln Concert, on Munich’s fledgling new-music label, ECM, broke records of all kinds. It remains the bestselling solo album in jazz, and the bestselling solo piano album in any genre.

From the glistening, patiently developed opening melody, through sustained passages of roaring riffs and folksy, country-song exuberance, the pianist is utterly inside his ongoing vision of the performance’s developing shape – a fusion of the freshness of an improvisation with the symmetries of a composition that’s central to the album’s communicative power. Harmonically and melodically, it wasn’t a particularly “jazzy” record by the piano-jazz standards of that time, which might also have eased its progress across the sectarian divides of jazz, pop or classical tastes. There had been, however, an earlier clue to the possibilities of this journey into the largely uncharted waters of improvised solo-piano performance. The great pianist Bill Evans, one of the young Jarrett’s jazz models and an artist similarly steeped in classical music, had recorded the meditative solo improvisation Peace Piece 16 years before, and built it around a simple two-chord vamp in which the harmonies stretched increasingly abstractly as the performance progressed. Much of Jarrett’s playing on The Köln Concert similarly developed around repeating hook-like motifs, instead of unfolding over song-structure chord sequences as most bop-based jazz solos did.

Jarrett’s improvisation was also hypnotically rhythmic, bordering on mantra-like. He was unafraid to locate a compelling idea and stick with it, building intensity on a single rhythmic notion in a manner that still sounds urgently contemporary. A pop-like deployment of repetition, and a reassuringly anchored sense of tonal consistency – the latter occasioned by the pianist’s hugging of the acceptable middle-register of an otherwise tinny piano he had almost cancelled the gig to avoid – contributed to the music’s astonishingly organic feel.

Jarrett’s desire to make a solo-piano album had led to his earlier departure from Columbia Records, and to his relationship with the compatible Manfred Eicher of ECM (with whom he was travelling around Europe, jammed into a Renault 5, on the tour that included Köln), a visionary producer who heard new music in the same eclectic way. Though he was only 29 at the time of The Köln Concert, Jarrett had already had a brief flirtation with electronics in Miles Davis’s fusion band (declaring afterwards that he wouldn’t touch a plugged keyboard again) and rich regular-jazz and early-fusion experiences in the popular bands of saxophonist Charles Lloyd and drummer Art Blakey. He had also made some compositionally distinctive and now highly regarded postbop recordings of his own, in the legendary early-70s “American quartet” with saxophonist Dewey Redman, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Paul Motian. But Köln was Jarrett’s moment, and a turning point for the immensely influential ECM label too, which the album helped to bankroll for years to come.

The Köln Concert isn’t universally admired by jazz listeners. Some find it close to easy listening in its repetition of catchy melody, or a irreconcilable split from the jazz tradition in its avoidance of many of the genre’s familiar materials. But Jarrett’s remarkable output in the years since, his interpretations of classical works, reinvention of the Bill Evans-inspired conversational trio, engagement with everything from symphony orchestras to cathedral organs, and through it all an enduring popularity that sells out the world’s great concert halls months in advance, testify to his creativity and eloquence.

In 2006, he released a similarly unpremeditated solo-piano concert from Carnegie Hall that ran to 90 minutes and five encores. When I discussed it with him for the Guardian, Jarrett said: “My glasses were falling off, my pants were twisted up, I was sweating, crouching, standing up, sitting down, and I was thinking ‘nothing can stop me now’.” He also said he’d had the same feeling – of total trust in his imagination – on The Köln Concert more than 30 years before….by…John Fordham……~

Circumstances were inauspicious when pianist Keith Jarrett and ECM Records owner-producer Manfred Eicher rolled into Cologne, Germany, in January of 1975. Jarrett hadn’t slept the night before and was in pain. Worse, the Bösendorfer piano they’d requested had been replaced by an inferior model which, according to Jarrett, “sounded like a very poor imitation of a harpsichord or a piano with tacks in it.” Yet the hour-long solo concert he performed around midnight at the city’s opera house, wearing a brace and nearly falling asleep at his instrument, was a deeply entrancing meditation on rhythm, whose double-vinyl recording became both the best-selling solo jazz and solo piano albums in history. Jarrett’s extemporized fantasia drifts seamlessly from idea to idea, sometimes settling into a two-chord vamp for minutes at a time. More relaxed than most of his other solo recordings, it boasts a full complement of Jarrett’s whooping, sighing and foot-stomping affectations while still offering a ravishing introduction to the art of improvisation. Richard Gehr…Rolling Stone..~

Recorded in 1975 at the Köln Opera House and released the same year, this disc has, along with its revelatory music, some attendant cultural baggage that is unfair in one sense: Every pot-smoking and dazed and confused college kid – and a few of the more sophisticated ones in high school – owned this as one of the truly classic jazz records, along with Bitches Brew, Kind of Blue, Take Five, A Love Supreme, and something by Grover Washington, Jr. Such is cultural miscegenation. It also gets unfairly blamed for creating George Winston, but that’s another story. What Keith Jarrett had begun a year before on the Solo Concerts album and brought to such gorgeous flowering here was nothing short of a miracle. With all the tedium surrounding jazz-rock fusion, the complete absence on these shores of neo-trad anything, and the hopelessly angry gyrations of the avant-garde, Jarrett brought quiet and lyricism to revolutionary improvisation. Nothing on this program was considered before he sat down to play. All of the gestures, intricate droning harmonies, skittering and shimmering melodic lines, and whoops and sighs from the man are spontaneous. Although it was one continuous concert, the piece is divided into four sections, largely because it had to be divided for double LP. But from the moment Jarrett blushes his opening chords and begins meditating on harmonic invention, melodic figure construction, glissando combinations, and occasional ostinato phrasing, music changed. For some listeners it changed forever in that moment. For others it was a momentary flush of excitement, but it was change, something so sorely needed and begged for by the record-buying public. Jarrett’s intimate meditation on the inner workings of not only his pianism, but also the instrument itself and the nature of sound and how it stacks up against silence, involved listeners in its search for beauty, truth, and meaning. The concert swings with liberation from cynicism or the need to prove anything to anyone ever again. With this album, Jarrett put himself in his own league, and you can feel the inspiration coming off him in waves. This may have been the album every stoner wanted in his collection “because the chicks dug it.” Yet it speaks volumes about a musician and a music that opened up the world of jazz to so many who had been excluded, and offered the possibility – if only briefly – of a cultural, aesthetic optimism, no matter how brief that interval actually was. This is a true and lasting masterpiece of melodic, spontaneous composition and improvisation that set the standard….by Thom Jurek…allmusic…~

This lodestar 1975 set didn’t just prove that an improvised solo jazz piano record could find a mass audience; it also helped solidify the intense yet dreamy aesthetic of producer Manfred Eicher’s then-young ECM label. Jarrett lets loose a torrent of ideas on the piano, delighting even himself (which you can hear whenever he lets out one of his frequent vocalizations or foot-stomps). Whether he’s ferociously plugging away at a vamp or slowly building out a tender theme, he keeps a spellbinding intimacy central to his sound….~

I still remember my first encounter with Keith Jarrett’s album The Köln Concert, recorded 40 years ago this week.

I was a teenager browsing the jazz bins at a record store on El Camino Real in Palo Alto late one evening, when a store clerk put the new Jarrett record on the turntable. As the opening notes began reverberating through the aisles, I could immediately sense a change in the ambiance of the store. Customers looked up from the merchandise, and gradually focused their attention on the ethereal piano music coming out of the speakers.

Then something unexpected happened. Within a couple of minutes of the album going on the turntable, a customer walked up to the front desk to ask the name of the record. He immediately bought a copy. Soon a second customer did the same. Then a third. And a fourth.

Within ten minutes, the store’s entire stock of The Köln Concert had sold out.

Frankly, I was as surprised as the store clerk. I was very familiar with Jarrett’s work, and had just seen him perform a few months earlier with his quartet at an Oakland concert. I considered myself an admirer, and had recently devoured—that is not too extreme a word to use, given my enthusiasm—his two previous solo piano albums, Facing You and Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne. I knew his music inside and out, had studied it with the goal of unlocking its essence. But I was a jazz piano player who spent three hours per day in the practice room; latching on to a new Jarrett album was a natural thing for me to do. The real mystery was why all these other customers, who had been browsing through the rock and pop bins, were responding with so much enthusiasm.

One thing, however, was absolutely clear to all of us. Jarrett’s album didn’t sound like anything else in the music world in the mid-’70s. I was a college student at the time, and the most widely-played albums on campus were Frampton Comes Alive, Fleetwood Mac, and Songs in the Key of Life. Disco was still intensely popular and, in a few months, The Sex Pistols would record their first album. The Köln Concert, a shimmering and rhapsodic solo piano album, was nothing like any of those records.

Even when compared to jazz albums, Jarrett’s new sound was an outlier—this was, after all, the age of jazz-rock fusion, and the biggest-selling bands in the field were plugged-in electric groups. The hot jazz acts of the day were Weather Report, George Benson, and the high-octane fusion bands led by Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock.

The Köln Concert was the opposite of all that. Jarrett not only played the grand piano (increasingly referred to as the acoustic piano, at that juncture, to differentiate it from the electric keyboards of the era), but he played it with a degree of sensitivity and nuance that you couldn’t find elsewhere in commercial music. He even risked gentleness and sentimentality, with a heart-on-sleeve emotional directness that many jazz artists would have been embarrassed to emulate—especially in the mid-’70s, when irony was in the ascendancy as a cultural attitude.

Yet, in the coming months, I watched with amazement as The Köln Concert entered the mainstream culture, reaching an audience that I might have thought immune to the appeal of jazz piano. It eventually sold more than 3 million copies, and for a time ranked as the top-selling solo piano album in history.

And Jarrett did this by violating almost every rule of commercial music. The tracks on The Köln Concert were free-flowing spontaneous improvisations recorded live in concert in Germany. They lacked a holistic structure. Even worse, they were much too long for radio airplay. The opening cut was 26 minutes in duration, and the next two tracks were 15 minutes and 18 minutes long. Only the seven minute encore followed something resembling a song form, but even this sounded a world apart from the hit singles of the day.

You might think that jazz radio deejays would embrace this music. But even they were skeptical. The Köln Concert avoided most of the familiar syncopations and phraseology that permeated the other jazz albums in heavy rotation. Programming directors feared that they might alienate their core audience if they played music of this sort that, after all, didn’t really sound jazzy.

Yet somehow Jarrett bypassed radio, and managed to go viral via the oldest method of all, word of mouth and person-to-person contact with friends who already owned the record. These were people who didn’t listen to jazz radio anyway.

Huge sales are not always greeted with enthusiasm in the jazz community, and a backlash was inevitable in the case of The Köln Concert. But the emotional directness of the music, and its unabashed melodicism made this album especially open to critique from those who felt the jazz art form required something more abrasive and challenging to move forward. When the New Age music scene blossomed a few years later, with numerous imitators of lesser talent mimicking (and diluting) the aesthetic vision of the Köln improvisations, perhaps even Jarrett himself wondered at what he had wrought

I understand these criticisms, but don’t agree with them. Jarrett tapped into something fresh and honest at that concert. He created a visionary work that still rivets the attention of first-time listeners today—much as it did on that day in the mid-’70s when I first heard it in a retail outlet. The music has held up, indeed much better than many of the irony-laden projects that seemed so much more progressive at the time.

My only regret is that most of the audience that discovered Keith Jarrett with The Köln Concert never embraced the rest of his oeuvre. I would have been delighted to see Facing You or the Bremen concert or the Jarrett quartet albums of the period—and those of other deserving jazz artists—also find a crossover audience. From that perspective, the promise of The Köln Concert was never fulfilled.But I don’t blame Keith Jarrett for any of this. And he certainly can’t be faulted for his banal imitators, or chided for his sales. For his part, he hadn’t been aiming for a hit record, and (unlike many of his contemporaries on the jazz scene) never made the slightest attempt to jump on trends, or even embrace the accepted formulas of commercial records. Moreover, he never tried to recreate the special ambiance of the Köln performance. He viewed this concert as a one-time event. He simply trusted in his music, in his preparation and talent, and then bravely thrust himself into the inspiration of the moment. And, after all, isn’t that what jazz is all about?…by…TED GIOIA …~

I have a friend who is one of the kindest, most generous and straight forwardly nice people that there could be and yet he is very, very irritating. I once shared a house with him and after 12 months I wanted to strangle him and bury him in the cellar. I have the same sort of uncertain response to Keith Jarrett. I came to jazz in my late teens and like many people of my generation it was through Miles Davis’ electric music - but at about the same time I happened to hear Keith Jarrett on an arts TV program and it blew my mind (as we no longer used to say back then because it was too old fashioned). I found his playing stunning - it was all solo work on the program - but I also found the idea of him coming onto the stage without a plan and just improvising for an hour or however long stunning. And that is what he does here. Perhaps because he was one of my first loves when I was responding to music in a new way - I was trying to listen to and understand the music as music rather than thinking about the words (I was a big Dylan fan through my teens) - Jarrett’s music always has a big emotional impact on me, but perhaps some of my uncertainty is that I want to distance myself from the 19 year old enthusiast. The strengths of this album seem obvious: it is a tour de force, it is accessible while seemingly complex, it is impassioned. A basic technique, method (I’m uncertain how to term it) during this concert is that with his left hand he plays rhythmic repetitions, at times sounding like the rhythmic loops in Steve Reich’s music, while with his right hand Jarrett plays exquisite melodies, often sounding deeply Debussian, yet always having a jazz sensibility - despite drawing on European concert music he always remains within the traditions of black American music. Part of the exhilaration of the music is that it brings together seemingly incompatible styles or forms and successfully synthesizes them. I’ve written in other reviews of Jarrett about the irritations of the music: easy hooks holding things together, a tendency to wallow in prettiness, the emotionally lazy effects. I don’t, however, regard his tendency to go on and on to be one of his faults: on this album, as on other concert recordings, it is the longer tracks that are the strongest - Part I and the second section of Part II. The shorter tracks can quickly show his irritations - the final section of Part II lazily keeps to its very beautiful melody but doesn’t do much with it, in the first section of Part II the repetitions dominate the variations - while in the longer tracks his strengths overwhelm the weaknesses. Although I find it a bit puzzling why this was the Jarrett album - and one of the few jazz albums - that seems to have reached out to a broader public, it remains a remarkable performance….by….onethink …~

The story behind this album always makes me think of Elvis Costello’s show in Utrecht on January 24 2005. It was a cold and snowy day in the Netherlands and Costello was having a cold. After a few songs he had very little voice left. When the audience convinced him to continue anyway he gave what is probably the best show I’ve ever seen him play. Sometimes singing around the high notes, missing a few notes or coughing in mid sentence, but the audience didn’t mind. Costello played with more intensity than he had in years and delighted the audience with a few surprising songs in the setlist. It was an unforgettable evening.

Exactly 30 years earlier, January 24 1975, Keith Jarrett arrived in Köln, tired after a long trip from Zürich, not having slept for 2 days and being forced to play on a poor, out of tune grand piano. After the concert promoter had to convince him to perform anyway, he gave a wonderful performance that remains his most popular recording ever and the best selling solo piano and solo jazz album. The piano had lots of shortcomings with malfunctioning pedals and weak low notes, but Jarrett works around it all and like Elvis Costello 30 years later in Utrecht the less than ideal circumstances inspire him to perform with an intensity rarely heard in music.

Strange, melodic, intense, experimental, beautiful, never boring, this remains one of the finest examples of jazz improvisation and solo piano music. With the music being so fascinating you don’t even hear the piano is out of tune or that the low notes sound very weak; it’s simply impossible to pay attention to anything else than the wonderful music. The fact that it was made in such difficult circumstances and that it’s all pure improvisation (Jarrett hadn’t made up a note of these 2 pieces before entering the stage) makes it even more remarkable. If you’re into jazz and for some reason haven’t heard this yet, go get it now. You really need it….by….mdekoning ….~

Amazing

This is an incredible achievement. I was hooked when listen to the first half of Part I. It was probably one of the most beautiful and inspired piece of music I have ever heard. The same thing happened with first part of Part II B.

The rest is also great but these moments are simply amazing. I cannot imagine how Keith managed to play this only by improvising. I don’t want to say anything more. Just listen and enjoy because this is from high spheres. Probably we are not supposed to hear something like this on this existence in flesh and bones….by…petrica …~

I have a confession to make. One that borders on blasphemy for a professed ECM fanatic such as myself: before writing this review I had never heard The Köln Concert. What is perhaps the most highly revered, and certainly the best-selling, album in the ECM catalog has managed to escape my ears all these years. Part of me wanted to save the experience for the right moment, while another had possibly been afraid that I might not like the album. Whatever the reason, I am happy to say that the wait is over…and it has been more than worth it.

The story behind this recording has, of course, already become the stuff of legend. On a dreary January day in 1975, Jarrett arrived at the Köln (Cologne) Opera House fatigued and malnourished and was bid to play on an inferior piano designed for rehearsals and not for live performance. As a result, the concert was almost never recorded. One can read about Köln lore ad nauseum elsewhere, not least in the album’s liner notes, so let’s have nothing more to do with it. The Köln Concert deserves to be listened to as it was created: without borders and without assumptions. And so, last night, as I lay awake in bed unable to sleep, I decided that it was time to fill this gaping hole in my listening life. With the lights already off, I put on the album and let the music take me wherever it wanted to take me. All I can offer in return is the following “travel diary” in honor of Jarrett’s achievement.

The opening chords of Part I set us upon an almost otherworldly path, providing gospelly signposts along the way to remind us of home. The music brims with the need for release, but Jarrett seems to want to hold onto it for as long as he can before its messages are lost forever. There is a persistence to his playing that speaks of countless internal dialogues all vying for attention. Delicate phrasing is suddenly punctured by a rhythmic depressing of the sustain pedal before flowering into an open exposition of higher energy. The music cascades as Jarrett’s voice careens off its towering contours when, just as suddenly, the majesty is swapped for an intimate chamber within its walls. Shadows of a former empire loom large, tethered by ecstatic cries.

Jarrett picks up the pace during the second act, moving from the elegiac to the frantic. Everything “fits,” joined by the same threads: a patchwork in which every seam is uniformly sewn. The progression is as lush as can be. It is as dense as a forest, and just as ordered in its own way. Jarrett brings us to a clearing, only to make us aware of the silence we left behind. So we turn around and jump right back into the thick of things as he expands his architecture to greater depths, carving out a subterranean labyrinth of cavernous sound that will never be charted again. The encore (labeled “Part IIc”) is both a montage of what came before and a preview for that which has yet to arrive.

It might seem clichéd to write this, but sometimes there are moments in one’s musical life that are simply magical. Clearly, Jarrett experienced over an hour’s worth of such moments here, and we are fortunate enough to be able to experience them ourselves, if only vicariously through the mediation of technology. Jarrett seems to know the piano’s vocabulary as well as his own speech, which might very well explain the involuntary vocalizations for which he is so often criticized. Structurally, the album could hardly be simpler: a series of vamps provide ample ground for floating improvised lines that stick primarily to the piano’s middle range. And yet, the scope of his vision is staggering in its implications. Jazz is Jarrett’s anchor, even if the voyage does carry him far beyond its generic boundaries. The applause only heightens the spell, reminding us that what we have just heard is indeed of this world, and was shared spontaneously with a crowd of our peers.

Despite what some might have you believe, by no means should this be anyone’s only Keith Jarrett experience. It needn’t even be one’s introduction. As sublime as it is, it is but one of many formative and breathtaking examples of his prolific output. This album is a lullaby for anyone who has no need for slumber, and Jarrett’s heartfelt voice explicitly conveys the rapture of living in the moment, his vocal interjections enhancing the “live” feel considerably and making for an even more visceral document….by…TYRAN GRILLO…~

Keith Jarrett is known as one of the best jazz musicians of all time, and this, the best-selling solo album in jazz history and the best-selling piano album, is the obvious reason why. Recorded at the Köln Opera House in 1975, this 66 minute solo piano concert manages to cover most every aspect of jazz improvisation to perfection.

This is some of the best jazz improvisation you will ever hear. Actually, I think that whether you like this album or not tells whether you like improv jazz or not. Keith Jarrett has skills. I mean, hearing this masterpiece of more than an hour’s worth of continuous, lush music, it is hard to believe that every note is spontaneous. Jarrett always seems one step ahead; being able to improvise over a two-chord vamp for 8 minutes while still keeping the listener hooked in emotionally; perfectly balancing focus on rhythmic figures, and meditation (at times, bordering to virtuoso self-oscillation) on droning harmonies and moody grooves.

Jarrett opens the concert by quoting the melody of the signal bell in the Köln Opera, which, very fittingly, is normally used to announce the beginning of a concert to patrons. From here on, he fluently pecks around various advanced harmonies, recalling his efforts from fusion-jazz, before diving into 12 minutes of extensive improvisation over a two-chord vamp. It is very trance-inducing but then again, the music is always moving and evolving; even when the foundation that is the bass seems repetitive, there is constantly little variations, which is truly impressive to witness, and so, even though it may at times seem mad and self-oscillating repetitive, you never doubt Jarrett’s genius nor the fact that you will be able to finally see the big picture of something that is purely spontaneous. I mean, the really impressive thing about The Köln Koncert is the feeling of an hour-long improvisation as being something meticulously planned because everything fits so perfectly into a whole.

The shear thought of all of this being improvised is impressive enough to leave you breathless, especially because it’s not only flawlessly executed; it is also full of personality. This album makes it obvious why Keith Jarrett is not only considered one of the absolute greatest jazz musicians of his own era but as one of jazz music’s most outstanding representatives….sputnik…~

The most improbably exhilarating record I’ve ever heard was recorded 40 years ago, at a special late show in the Cologne Opera House, in front of a youthful capacity crowd. It’s likely the only opera-related album I’ve ever listened to more than once, but that’s fitting, since few of the 1,400 young Germans in attendance on January 24, 1975 were regulars, either. They’d come that night to hear something even rarer and less commercial: an hour-long improvisation on solo piano by a 29-year-old Pennsylvanian named Keith Jarrett.

Perhaps you think that 60 minutes of unbroken, off-the-cuff doodling sounds indulgent and esoteric, in which case you’ve never heard The Köln Concert, the double-LP of the show released later that year. Perhaps you think that an entirely improvised live jazz album by a single musician must have been, at best, a cult object, in which case it might surprise you to learn that it turned Jarrett into one of the least likely pop stars in history; to date, it has sold an estimated 3.5 million copies, placing it alongside Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue as one of the most popular jazz records ever. By decade’s end, Jarrett would be release a 10-LP (!!!!) live album and perform solo on Saturday Night Live. In the words of Guardian jazz critic John Fordham, “His concerts began to resemble religious rituals, attended by flocks of devotees for whom his music had a meditative, spiritual, and transformative power.” The mid-'70s were a wild time.

When he arrived in Cologne, Jarrett was a young performer but a seasoned one, with nearly a decade of professional jazz-making already behind him. He’d played piano for saxophonist Charles Lloyd before joining Miles Davis’s band in 1970 and switching over to keyboard. This was a particularly tumultuous moment for Davis—his music had become unprecedentedly dense, expansive, and rhythmic, with songs often stretching to nearly a half-hour and featuring multiple drummers and bassists. The two Miles records that included Jarrett—Live at the Fillmore and Live-Evil—are some of the most frenzied and aggressive jazz ever put to tape, full of long, minimally harmonic arrangements and feral soloing. This was jazz as Afro-futurist squall, a Jackson Pollock deconstruction of Duke Ellington’s famed “jungle sound” from the 1920’s. But Jarrett, a seeker type and a musical prodigy, needed more space for expression than that hurricane allowed.

He left the group in December 1971 and was soon approached by Manfred Eicher, a German national who had recently started his own imprint, ECM Records. Eicher lured Jarrett with the promise of absolute artistic freedom, and the pianist obliged with a studio recording, Facing You, made up of solo improvisations. The polar opposite of Davis’s cacophony, this playing was marvelously clean, direct, and acoustic, as approachable as pop without any of the rock-audience pandering that marked many fusion groups of the time. The record was a small success, particularly among jazz fans, and Eicher decided to take Jarrett on the road.

Europe was in many ways a more friendly audience for jazz musicians than America at the time. While the number of Stateside jazz clubs shrank throughout the '60s, the music was brandished by younger Europeans as a revolutionary totem. Artists from throughout the continent, like Poland’s Tomasz Stanko and Norway’s Jan Garbarek, endowed jazz with new tonalities that strayed far from the blues, bop, or cool modal approaches developed in the U.S. But European audiences were also hungry for American performers, and Jarrett was a known quantity, having toured prodigiously overseas as a member of Lloyd’s and Davis’s bands. Eicher started him on a regular circuit of European markets whenever his schedule allowed, and Jarrett developed his fully improvised style in places like Bergamo, Bern, Geneva, and Molde. Most nights he would play two half-hour movements followed by a five-minute encore; a typical performance would glide between extended, almost gospel-like rhythmic passages and lyrical, balladic sections, often devolving into freer, atonal moments along the way.

Jarrett became a phenomenon, as much for the audacity of his method as for the strangeness of his stagecraft. He often resembled a gymnast more than a pianist—standing up, wildly contorting his arms, breathing heavily, and chanting along with his melodies. His concerts were feats of athletic as well as creative stamina, but there was a deep spiritual element to them as well, as Jarrett made clear in the liner notes for his first live ECM recording, the triple-LP set Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne, released in 1973. Declaring himself to be on a distinctly untrendy “anti-electric crusade,” Jarrett further explained himself:

I don’t believe I can create, but that I can be a channel for the Creative. I do believe in the Creator, and so in reality this is his album through me to you, with as little in between as possible on this media-conscious earth.

This kind of vague religious psychobabble and pop-skepticism likely fits well within your conception of 1973, the heyday of Mother Earth News, Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps, and the Back to the Land and communal-living movements. Within a few years, DownBeat would describe Jarrett’s droning, meditative sections as “sonic mandalas,” while Melody Maker would suggest that his music enforced a “hands clasped and kaftans on” vibe. But the very fact that his music was being covered in the pop-minded and jazz-averse Melody Maker at all was proof of how deeply aligned Jarrett was with other musicians of the time: He evinced and echoed the passionate drones of Ravi Shankar, the purposeful repetitions of James Brown, and the wildly ambitious structures of Soft Machine and Yes, not to mention the proud sonic primitivism of Neil Young.

Which is all to say, the world was ready for The Köln Concert, or at least more prepared for it than might be assumed 40 years on. Certainly the mood was right in the opera house itself, where Jarrett was booked as the fifth show in the so-called Jazz at Cologne series, organized by a teenaged aficionado named Vera Brandes. Selling tickets at only four German marks apiece, Brandes ensured a full house, almost all of the attendees around Jarrett’s age. For his part, he took the stage looking “fresh from the musical Hair,” as one onlooker recently told the BBC….by…John Lingan….~

If blogs had been around in the late 70s or the 80s I wouldn’t have thought for a second to write about Keith Jarrett’s watershed album The Köln Concert, because every jazz enthusiast with a computer keyboard and a Blogger account would have already been flooding the internets with praise about this record. Three and a half decades after its 1975 recording and subsequent release, it remains the record people most identify with Jarrett, and in all likelihood, ECM Records’ all time best seller. But enough time has passed to reflect again on the significance of this record, a timeless recording whose fame was nevertheless rooted in the timing of its release.

By the mid 70s, jazz was dominated by rock-jazz fusion. This sub-genre of jazz had gotten off to a terrific start, but eventually, much of it became over-composed, over-produced and full of bravado. What was gained in proficient musicianship was more than countered by the loss of swing, soul and substance. Sure, there were some notable fusion records of that era and many of them even raved on here, but increasingly, jazz-rock was offering little to offer over what you could get from rock itself. Some of jazz’ most respected players like Jackie McLean, McCoy Tyner and Dexter Gordon stubbornly stuck with acoustic post-bop jazz and paid the price by being driven into obscurity and in some cases, near poverty.

The first flicker of hope in the eventual resurgence of unplugged jazz came one day in January, 1975 when Keith Jarrett sat in front of piano in a Köln, West Germany opera hall and began to play melodies that didn’t exist before that moment. A few years earlier, Jarrett had ironically been a soldier in the movement to rockify jazz as a member of Miles Davis’ band for about 18 months from 1970 to 1972. It’s a stint he’s since disowned, and not long after he left, Jarrett became as likely to play any plugged-in instrument as Marie Osmond was likely to have a tryst with George Clinton.

Around the time he was wrapping up his gig with Miles, he recorded his first solo piano—and ECM—record Facing You (1971) that while taped in the studio, paved the way for Köln a few years later.

Jaunty or reflective, soulful or swinging, Jarrett opened up his heart and played whatever notes felt right at the moment. Missing from the show was overly flashy displays of instrumental prowess; instead of being found playing the perfect lick, Jarrett chose instead to get lost in the melody. He used virtuosity to advance, get this, art instead of science.

Jaunty or reflective, soulful or swinging, Jarrett opened up his heart and played whatever notes felt right at the moment. Missing from the show was overly flashy displays of instrumental prowess; instead of being found playing the perfect lick, Jarrett chose instead to get lost in the melody. He used virtuosity to advance, get this, art instead of science.

The reaction to this recording is nothing like ECM or Jarrett had probably expected. After all, it went against the prevailing rules. It returned an idiom to its basic values, in a sense, just when its public was ready for that kind of shift. It went by feel, not flash. Keith Jarrett did for jazz what the Ramones did for rock just one year later.

The Köln Concert didn’t single-handedly bring jazz back to its roots; The Köln Concert isn’t even a “jazz” record except in a loose sense. It took several more events to rekindle interest in acoustic and/or lighter jazz on a broader scale: the emergence of both Pat Metheny and Wynton Marsalis, among other things, finally swung the pendulum firmly back in the other direction. But Jarrett revealed a lot of untapped interest in both, as long as the music was honest and fresh. And thirty-five years later, The Köln Concert sounds as fresh and honest as it did when these songs were composed, in front of a live audience….by S. Victor Aaron…..~

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of this landmark recording (the best-selling solo album in jazz history), ECM has released the double vinyl set in a 180-gram audiophile pressing. The sound is a revelation. Every note and nuance of Jarrett’s amazing dynamic touch on the Bosendorfer baby grand fills the Köln Opera House with radiance. Four decades later, one still gets an emotional/nostalgic charge from the rhapsodic right-hand runs, the dramatic intervallic stabs and driving resolution of “Part I,” the rolling, gospel-tinged flurries of “Part IIa,” the somber introspection and mesmerizing folkloric vibe of “Part IIb,” and the bittersweet, hymn-like “Part IIc” (by far the shortest and most memorable of the four sides). For those of us who came up in the late 60s/early 70s, this music is imprinted on our memory banks as deeply as Sgt. Pepper’s or Bitches Brew. We’ve memorized every passage, odd yelp, passionate moan, or foot stomp by the theatrical enfant terrible. A time machine trip for some, this 40-year-old document may also hook a new generation. From rare delicacy to cathartic tension and release to giddy exuberance, The Köln Concert is still a feast for the ears. ….. by Bill Milkowski ……~

Tracklist

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part I 26:15

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part II a 15:00

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part II b 19:19

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part II c 6:59

gramophone

Music, music forever

Crazy with music

vinyl

Rock n` Roll

Vinyl forever

The Köln Concert didn’t single-handedly bring jazz back to its roots; The Köln Concert isn’t even a “jazz” record except in a loose sense. It took several more events to rekindle interest in acoustic and/or lighter jazz on a broader scale: the emergence of both Pat Metheny and Wynton Marsalis, among other things, finally swung the pendulum firmly back in the other direction. But Jarrett revealed a lot of untapped interest in both, as long as the music was honest and fresh. And thirty-five years later, The Köln Concert sounds as fresh and honest as it did when these songs were composed, in front of a live audience….by S. Victor Aaron…..~

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of this landmark recording (the best-selling solo album in jazz history), ECM has released the double vinyl set in a 180-gram audiophile pressing. The sound is a revelation. Every note and nuance of Jarrett’s amazing dynamic touch on the Bosendorfer baby grand fills the Köln Opera House with radiance. Four decades later, one still gets an emotional/nostalgic charge from the rhapsodic right-hand runs, the dramatic intervallic stabs and driving resolution of “Part I,” the rolling, gospel-tinged flurries of “Part IIa,” the somber introspection and mesmerizing folkloric vibe of “Part IIb,” and the bittersweet, hymn-like “Part IIc” (by far the shortest and most memorable of the four sides). For those of us who came up in the late 60s/early 70s, this music is imprinted on our memory banks as deeply as Sgt. Pepper’s or Bitches Brew. We’ve memorized every passage, odd yelp, passionate moan, or foot stomp by the theatrical enfant terrible. A time machine trip for some, this 40-year-old document may also hook a new generation. From rare delicacy to cathartic tension and release to giddy exuberance, The Köln Concert is still a feast for the ears. ….. by Bill Milkowski ……~

Tracklist

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part I 26:15

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part II a 15:00

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part II b 19:19

Köln, January 24, 1975 Part II c 6:59

gramophone